Professor of Nursing at Duquesne University

Why is the American health care system so difficult to navigate? People identify difficulties in access, cost and quality as the main issues they encounter when seeking medical assessment and treatment.1 Access refers to the person being examined by the right provider, and in the right setting, for their presenting symptoms and given the correct diagnosis, tests and treatment.2 Cost means that the appropriate treatment and care is paid for by the patient, insurance companies and/or the government. Quality is outcome-oriented and includes more than satisfaction with the provider, setting and treatment. Today, quality of care means that the treatment produces a good or improved outcome, ideally better health.

While access, cost and quality are easy to define, they are hard to implement. The barriers to access for patients include: lack of knowledge, uneven geographic distribution of primary and specialist care providers, no or inadequate insurance, lack of transportation, poverty and limited office or clinic hours.

The United States has the costliest health care system in the world. It is also the only high-income country that does not provide health care for all its citizens.3 In America, health care is a business rather than a benefit. Because of the separation of the health care system between the public (government) and private sector, people receive health insurance from their employers, the government (Medicare, Medicaid or State Children's Health Insurance Program) or private insurance companies, or they pay out of pocket.

The government has tried to reduce the cost of care through approaches like managed care, bundled payments, Medicare Advantage (also known as Medicare Part C) and rewarding providers if treatments are successful. Another cost-saving and quality-enhancing plan seeks to have hospitals improve care coordination and reduce avoidable readmissions.4 For more than a decade, Medicare has been financially penalizing hospitals with too many avoidable readmissions for certain conditions.

The need for greater alignment between care and insurance reimbursement extends beyond hospitals to home care. When I was a visiting nurse in Pittsburgh, where a large segment of the population was Eastern European, many of our patients were middle-aged women whose parents were immigrants from that region. Several of these patients suffered from debilitating leg ulcers. Because these lesions were usually infected and located on their lower legs, far from their hearts, they were difficult to heal. Most of the women had difficulty walking and managing household tasks. If the wounds failed to heal after a number of home care visits, the visits were no longer covered by their insurance companies, though the patients may have benefitted from additional care. While patients could pay out of pocket, the insurance companies only paid for treatment that was successful.5

These women found themselves in a difficult position. Although they had health insurance, the illness for which they sought treatment was chronic and very slow to respond to care. Their infected legs had been treated with antibiotics, but the infections returned. The compresses and dressings were challenging to carry out alone without assistance. When a successful outcome was linked with insurance payment, the patient's only choice was to self-pay.

This is only one scenario out of many that exemplifies how a "one-size-fits-all" approach to care for treating conditions is not always successful in achieving positive outcomes for patients. Consideration of patients' environment, support networks, lifestyle, socioeconomic status and other factors is essential when developing plans of care.

BEYOND ACUTE CARE

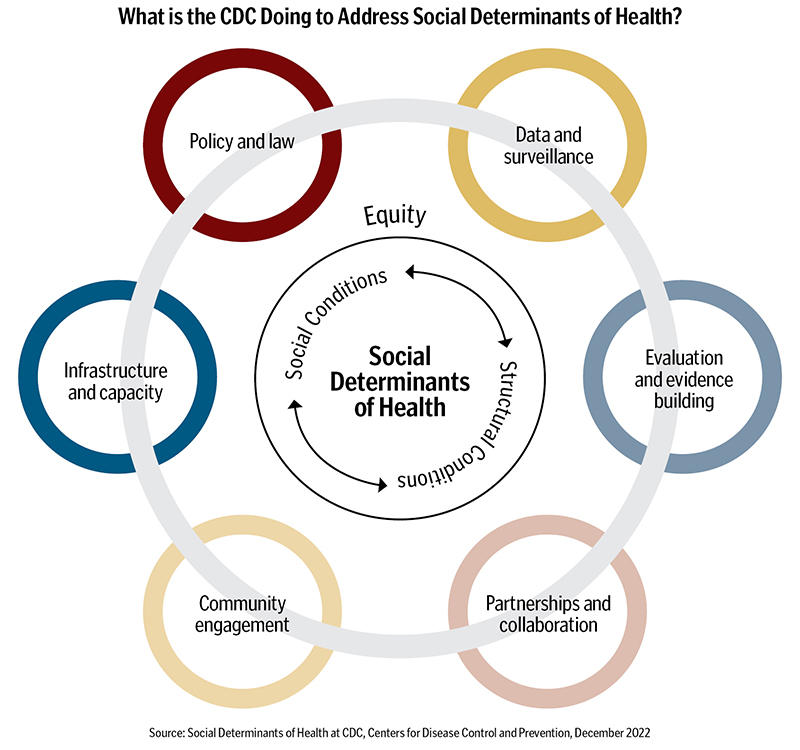

What characterizes the American health care system? The American health care system is intensive and oriented to the treatment of acute illness. In recent decades, health systems and care providers have emphasized greater attention on the social determinants of health as significant factors in reducing costs and improving care outcomes.6 As noted on the diagram on page 39, these social determinants include social and structural conditions associated with health and well-being.7 While the social determinants of health look beyond biology and disease, they do not provide a road map for accessing health care or improving quality. To do that, lawmakers and community organizations must analyze existing laws and programs, review data and outcomes, and work for policies and practices that may improve social determinants to help influence the health status of individuals or groups. Understanding the impact of social determinants on health outcomes, community organizations, local and state governments and insurance companies are developing partnerships to support food banks, build safe and affordable housing and help people find and keep jobs.

NAVIGATING COMPLEX SYSTEMS

Members of the public don't always know how to navigate care systems in the ways that those working in health fields do. To obtain health care, they're required to locate a primary care provider or a specialist. While patients may ask a primary care provider for a referral, they may also consult their friends, the nurse down the street or visit providers' group websites. Their choices depend on the quality of information they receive.

To access care, patients also have to find their way through an office complex or a hospital labyrinth. Hospitals have several wings, many added after their original construction. Sometimes complex directions are displayed with arrows posted in hallways or via drawn maps on the floor. Others have receptionists or apps to help patients and visitors locate rooms or treatment areas. Those who work in health care might want to ask their friends or family if they were greeted warmly in a health care setting, if they understood how to get from the parking garage to the room where they needed to be, and how long they had to wait for an appointment. A person new to these environments may provide insight on how much navigating and waiting patients may need to do to access care.

Access to treatment becomes more complex if the patient or family is dissatisfied with the care they receive. Resourceful patients know that there are ideally many hospitals and specialists in the area. He or she can request a new doctor, transfer to another hospital or travel to a specialized diagnostic center. However, for patients who do not understand their rights and need a nurse advocate, how would they know to ask for one? Does your system have anything in place to identify patients who might benefit from having a navigator or advocate? Many patients are trapped by their illnesses and their lack of knowledge and energy. This may prevent them from seeking resources or advocating for the best care, treatment or care team to address their needs.

Access to care can be more complex in outpatient settings. If a patient has an established relationship with a provider, he or she is told when to return for a follow-up visit. However, new patients need to call or make appointments online. Many providers' offices do not answer their phones. Voicemail instructs callers to leave details to make their appointments: their names, phone numbers, birthdates and the name of the provider they wish to see. Many people spend hours trying to schedule medical appointments.

Some providers are more accessible than others. However, the average wait time for a specialist is 26 days. In the Pacific Northwest, dermatology patients may wait as long as 84 days to see a new dermatologist.8 For patients trying to get an appointment with a cardiologist, the average wait time can be as long as 26 days, while for obstetrics/gynecology, patients may wait an average of 31 days.9

Some large academic centers have found ways to increase access to providers beyond painting directional arrows on hospital floors. Many employ concierges or navigators who use emails or telephone calls to manage a panel of patients. They remind patients about appointments, tell him/her what documents to bring and provide directions to the clinic. If the person will be having a test, they review pretest guidance. These steps can help make an appointment go more smoothly.

CHANGING RELATIONSHIPS, CLEAR COMMUNICATION

When I was a young nurse, only physicians discussed diagnoses and treatment plans with patients. Patients were not always well-informed. This was before smartphones and the internet. Some physicians were militant in protecting their authority.

I remember a gentleman in his early 50s who had terminal cancer. He was an economist employed by a large bank in Pittsburgh who advised bank managers about the size of their loans based on his assessments and predicted outcomes. As he discussed how he made a living, I saw the irony of his situation: Here was a man who advised large banks about their investments, yet he could not get information about his own illness.

Each day, he asked me about his illness/prognosis. I relayed his questions and his background to his physician, however I was not able to convince the physician to talk with the patient about his illness. While this physician does not represent all providers, he represents an era in medicine when the physician was the captain of the ship. The next time the patient asked me what was wrong, I added to my usual answer, "You have to talk with the doctor." I asked him what he thought was wrong with him. He said, "I think that I have cancer and do not have long to live." Not long after that, he died. I thought of him every time I passed a particular restaurant that he had done a loan assessment for prior to his hospital admission.

Some families also withhold information from their loved ones. My father had one brother. Their sisters had died as young girls. My father and his older brother were very close and talked with each other every day. My uncle had been hit by a car in downtown Pittsburgh. He had back pain and was on bed rest at home. My father visited him several times a week. One afternoon when my dad and I were visiting, I noticed a bottle of medicine and recognized the pills as hormones used to treat prostate cancer. When I got home, I called his oldest son, my cousin, and asked if his dad had cancer. He did not answer me, so I asked again. He said, "You know what is wrong with him." I told him that I would tell my father what I thought was my uncle's diagnosis. When I told my dad, his eyes filled with tears. He said, "I was afraid of that, I remember Mom and Pop."

It is less common to keep a serious diagnosis from patients, but power structures and fear of illness or death continue to mar doctor, patient and family communications. Teaching and using effective communication techniques and explaining medical realities clearly need to be an essential part of care.

HUMANIZING CARE

A diabetologist in Washington, D.C., who treated children and adolescents, practiced in three clinics in the district and one in Maryland. Among her patients — many of whom were on insulin pumps — there were striking differences in the socioeconomic status of the children who went to the hospital clinic. Children from families who were poor went to the hospital clinic because they depended on public transportation. Some had to take two or three buses to get to the clinic and were often late to their appointments to have their blood sugar measured.

Those who were late had to go to the lab to have their blood drawn and then return to the clinic. Most of the clinic doctors would tell the staff to cancel the appointment if the family was more than 10 minutes late. The hospital clinic had a high percentage of Black patients, and canceling appointments created a barrier to care. Canceling appointments did not please the diabetologist, who instead ignored the instructions from the doctors and waited for the patients. It was important to her that the children received appropriate care.

How can care providers help their patients to better navigate the health care system? They can begin by trying to listen, understand and adapt to patients' needs and situations, and to avoid making assumptions. Additionally, providing better access to care through coherent navigation can be helpful. As noted earlier, concierges, receptionists and clear signage help. However, all providers can review and potentially improve the information and instructions provided on their websites and voicemails. Websites that address commonly asked questions are helpful and can be easily updated.

WE NEED TO CONTINUE TRYING

Decreasing health care costs and improving outcomes requires collaboration among providers, hospitals and clinics, the government (especially members of Congress) and insurance companies. Patients can help by not demanding unnecessary tests, not requesting the newest, most expensive drugs and by taking responsibility for their personal health. Currently, insurers and the government withhold funds from providers, hospitals and patients if the outcomes are not good. What would happen if they were rewarded when costs were decreased and outcomes were improved?

Illness and death are part of the life cycle. No matter how hard anyone tries, errors will occur, some bad choices will be made and desired outcomes will not be realized. However, everyone can try. We need to work for strong personal relationships and systemic change to bring about needed improvements.

SR. ROSEMARY DONLEY is a professor of nursing and holds the Jacques Laval Chair for Justice for Vulnerable Populations at Duquesne University School of Nursing in Pittsburgh.

NOTES

- Dana P. Goldman and Elizabeth A. McGlynn, U.S. Health Care Facts About Cost, Quality and Access (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2005).

- "Care Coordination," Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, August 2018, https://www.ahrq.gov/ncepcr/care/coordination.html.

- Eric C. Schneider et al., "Mirror, Mirror 2021: Reflecting Poorly, Health Care in the U.S. Compared to Other High-Income Countries," The Commonwealth

Fund, August 2021, https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2021/aug/mirror-mirror-2021-reflecting-poorly. - "Hospital Readmissions Reduction Program (HRRP)," Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, https://www.cms.gov/medicare/medicare-fee-for-service-payment/acuteinpatientpps/readmissions-reduction-program.

- "Wound and Ulcer Care," Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, October 7, 2021, https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/view/lcd.aspx?lcdid=38902.

- Richard C. Palmer et al., "Social Determinants of Health: Future Directions for Health Disparities Research," American Journal of Public Health 109, no. S1 (January 2019): S70–S71, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30699027/.

- "Social Determinants of Health at CDC," Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, December 2022, https://www.cdc.gov/about/sdoh/index.html.

- Sara Heath, "Average Patient Appointment Wait Time Is 26 Days in 2022," PatientEngagementHIT, September 15, 2022, https://patientengagementhit.com/news/average-patient-appointment-wait-time-is-26-days-in-2022.

- Heath, "Average Patient Appointment Wait Time."