Lack of resources remains pressing problem

By JULIE MINDA

Even though the availability of palliative care services has been increasing steadily in the U.S. over the past two decades, significant gaps remain. It can be especially difficult for people in rural areas and people who are not hospital patients to access such care. And there are some minority groups that use palliative care at a much lower rate than white people do.

Dr. Donald McDonah visits a hospice patient at St. Joseph Hospital in Nashua, New Hampshire. The patient died several months later at home. McDonah is the physician member of the palliative care program at the hospital. He says the hospital is looking at how best to expand palliative care services to more people in need.

Much remains to be done to meet the full promise of palliative care, program administrators in the ministry said.

As they work to offer palliative care services including pain and symptom management to more patients and in more venues, they do so knowing demand won't automatically follow supply because too many people in the public and in the health care profession don't know what palliative care is. To move the needle on palliative care, proponents see a need to educate not only patients, but also in many cases doctors, other clinicians and health executives.

Increasing reach

Efforts are underway to add palliative care to the tool kit of general practitioners and specialists in other fields. Ascension is among systems integrating palliative care into cardiac and cancer care management pathways to ensure patients have timely access to supportive care.

Others are trying to increase the reach of palliative care by educating consumers so they'll know to ask for the services when they or a family member could benefit. The Caring for the Whole Person Initiative funded by CHA and two Catholic health systems in California is a national pilot to promote the uptake of palliative care in part through parish-based education.

The Archdiocese of Boston, which successfully fought against assisted suicide legislation in Massachusetts, is taking palliative care education into parishes, high schools and grade schools.

McDonah

Dr. Donald McDonah is the physician member of the palliative care program at St. Joseph Hospital in Nashua, New Hampshire, part of Covenant Health. McDonah and his staff are exploring how best to promote palliative care in the hospital's catchment area, and particularly in communities that have little access to — or knowledge of — palliative care. "We don't do well when we go in and try to tell people what we think they need. We need to listen" and then respond to what they say, he said.

Gaps remain

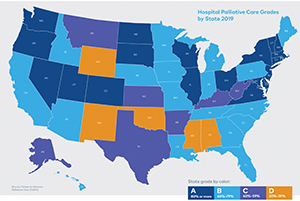

A 2019 report, "America's Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation's Hospitals," says while palliative care services have expanded greatly over the last two decades, "access is determined not by patient need but by where a patient lives or the type of hospital (factors such as hospital size or tax status) to which they are admitted." Only 17% of rural hospitals with 50 or more beds had a palliative care team when the report was published.

Arneson

Dr. Francine Arneson is a palliative medicine physician with Avera Medical Group and medical director of the palliative care program for Avera McKennan Hospital & University Health Center in Sioux Falls, South Dakota. She said the palliative care fee and reimbursement structure can make it difficult to secure the financial and human resources needed to expand access.

Avera Health, the regional health system parent of Avera McKennan, built one of the nation's most comprehensive telehealth services to bring specialty care including palliative care to rural communities and small towns across South Dakota and adjacent pockets of Minnesota, Iowa, Nebraska and North Dakota.

Berke

But unequal access remains a big issue. Charlene Berke, a project director for a grant-funded palliative care program at Avera Sacred Heart Hospital in Yankton, South Dakota, explained that few residents of Native American communities and reservations in Avera's service area have heard of palliative care and many likely couldn't access the services if they wanted to.

Native Americans can be difficult to reach with services because many live in remote areas that are not wired with the technology needed for telemedicine access, said Arneson.

Berke said even in areas where palliative care is available, health care professionals may conflate palliative care with hospice. St. Joseph's McDonah added that large swaths of the public don't know what palliative care is — "no one knows how to spell it or say it" — or they confuse it with hospice and believe it's only for the dying.

McDonah noted that in Nashua palliative care was until recently available only in the hospital and mainly to inpatients. Last month the hospital opened an outpatient palliative care program on campus, offering in-person and telehealth appointments.

Most palliative care services in the U.S. are hospital-based and that has presented its own obstacles, said McDonah. The uninsured and poor patients may be reluctant to seek hospital-based palliative services out of concerns over cost, although some may qualify for income-based discounts or free care. Additionally, he said, those who are poor, including people who are homeless, may not have transportation to get to an appointment.

Ruiz

Cathi Ruiz, a hospice and hospital chaplain at Adventist Health Sonora, is a volunteer in the Caring for the Whole Person Initiative. She said in her rural California community in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, few of the Hispanic residents know about palliative care services — though information is reaching some of the most vulnerable individuals as the church- and CHA-sponsored initiative equips parishes to provide volunteer support to parishioners who are seriously ill or dying.

Ruiz teaches the volunteers at St. Patrick Church in Sonora, California, to explain the potential benefits of palliative and hospice care and how to access the services to infirmed patients they visit. She said of the Caring for the Whole Person Initiative: "It's about building trust, not making assumptions, not being judgmental, not giving opinions. It's about doing all this, and directing people to resources."

Palliative care service administrators' concerns over inequitable access are borne out in a survey of research literature published in the Dec. 8, 2020, American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine. The authors of "Disparities in Palliative and Hospice Care and Completion of Advance Care Planning and Directives Among Non-Hispanic Blacks: A Scoping Review of Recent Literature," wrote that "available data points to significant barriers to palliative and end-of-life care among minority adults. … There are also geographic disparities in access to palliative care in (the) United States, suggesting that access to such care is worse among more racially diverse, poorer, and more politically conservative states."

The Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center in 2019 published a report card on how states rate when it comes to access to palliative care. This map from the report shows what percentage of hospitals in each state have a palliative care program. The report is titled "America's Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation's Hospitals."

The authors said the literature specifies race and culture as the main barriers preventing non-Hispanic Black patients from receiving effective hospice and palliative care. "An important challenge is to develop an understanding of how race/ethnicity, cultural values, and preferences of non-Hispanic Black patients and their families lead to disparities in palliative and end-of-life care," they conclude.

Making the case

Arneson in South Dakota, McDonah in New Hampshire and Kyle Terry, who directs the hospice program at Saint Francis Health System of Tulsa, Oklahoma, are among the providers across the U.S. documenting palliative care's effectiveness in care improvement and cost avoidance to support the case for service expansion.

For now, the service expansion they are implementing is incremental. McDonah said St. Joseph plans to use a mobile unit to offer palliative care education and services in underserved Nashua neighborhoods where there are concentrations of people who are poor, uninsured and unhoused.

Avera has two grants that pay for outreach education on palliative care. Berke said the first program builds awareness of the hospital's palliative care offerings among rural health care providers, students studying for health careers, community members and patients. A separate five-year grant supports the sharing of culturally relevant information on and access to palliative care on Cheyenne River, Pine Ridge and Rosebud Sioux Native American reservations.

Under the latter grant, Avera is talking with cancer patients, caregivers, tribal leaders, healers and health care providers to learn their perspectives. It plans to use that information to develop a palliative care educational program and tool kit for health care providers serving the tribes. Avera also is providing a health care liaison for palliative care patients living on the reservations as well as for their families.

The California Catholic Conference has created this video to explain the Caring for the Whole Person Initiative.

CHA convenes palliative care council, assists ministry in creating care standards

In the year since the Supportive Care Coalition became part of CHA, the association has learned through surveys and other contact with members that a top priority when it comes to palliative care is to standardize and expand services.

CHA has developed these and other resources for use by palliative care teams across the ministry.

Shortly after it brought the coalition into its fold, CHA invited 31 former members of the Supportive Care Coalition board and 33 additional hospice and palliative care leaders from Catholic health care systems across the U.S. to identify their priorities around palliative care. Just over 80% of the 26 respondents said a top priority is reducing clinical variation in Catholic-sponsored palliative care programs. This includes having program development tools, electronic health record dashboards and outcome measures to align palliative care programs with the Joint Commission and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care's "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care," now in its fourth edition.

Respondents also said it is a high priority for Catholic-sponsored palliative care programs to expand such services beyond the acute care setting. This includes using telehealth to reach rural and other underserved communities. Payment reform and advocating for legislation and policy to advance palliative care workforce development and foster innovative care models were among the respondents' priorities.

CHA invited 12 palliative care and hospice leaders from around the ministry to address these priorities as members of its newly formed Palliative Care Advisory Council. That council met for the first time in December.

Many of the council members had been on the board of the Supportive Care Coalition. The coalition was founded in 1994 to counter state-level efforts to legalize assisted suicide by improving the care and reducing the suffering of seriously chronically ill and dying patients. At the time it joined CHA, it had 14 members, including 11 Catholic health systems, two long-term care providers and the Archdiocese of Boston.

Hess

Denise Hess, CHA director of supportive care, was executive director of the Supportive Care Coalition when it merged into CHA in January 2021. She is the CHA staff lead of the Palliative Care Advisory Council.

She said the initial focus of the council will be to assist CHA members in participating in the efforts of the Palliative Care Quality Collaborative by contributing to a national palliative care registry that tracks adherence to the guidelines established by the Joint Commission and the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care.

According to Hess, without the involvement of the CHA advisory council, many Catholic palliative care providers may not learn about the existence of the registry, nor its potential to advance palliative care quality. CHA has hosted sessions where representatives of the nonprofit Palliative Care Quality Collaborative teach participants to document, track and report on their palliative care programs, the composition of their palliative care teams, the way they market services and other aspects of the palliative care services they offer. Palliative care consultations, chronic pain management and home palliative care visits are among the services being tracked.

Members of the Palliative Care Quality Collaborative can use its pooled data and metrics to benchmark how they are doing against other providers and then to build up their services where there are gaps. CHA's endorsement of the Palliative Care Quality Collaborative's work already has resulted in more Catholic health systems joining that effort and entering their information into the registry, according to Hess.

She said that being part of this standardization work and using benchmarks can help palliative care administrators to illustrate to their systems' executives where their respective organizations may be falling short. The comparison may help those palliative care leaders to gain support to increase the resources their systems dedicate to holistic care and symptom management for the chronically ill and dying.

Hess said research has shown that bolstering palliative care services can boost patient and clinician satisfaction, improve health care outcomes and reduce hospital readmissions, among other benefits.

Hess said once the council helps CHA members to make headway on care standardization, the council will focus on other palliative care priorities that CHA members have identified, such as the need for service expansion and for increased advocacy efforts.

—JULIE MINDA

Both palliative care and hospice care focus on symptom relief, quality of life and family involvement in serious illness. Such care is holistic, collaborative and usually delivered by a team of specially trained providers, according to CHA. While palliative care is for any person suffering from a serious chronic illness, hospice is for terminally ill patients who are not expected to live longer than six months.

The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care outlined a national standard of care for palliative care programs and services in its "Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care." However, in practice, the guidelines are followed unevenly, and there is wide variation in programs, according to Denise Hess, CHA's director of supportive care.

While it is common for a large hospital's palliative care team to include doctors and nurses, social workers, nutritionists, and chaplains, some palliative care practices are much smaller. Many are led by registered nurses or advance practice nurses.

Palliative and hospice services aim to manage pain and other symptoms, address the patient's emotional health, coordinate care and improve communication between providers and patients, and align care and decision-making with the individual patient's goals. Catholic programs generally include a spiritual care component.

Palliative care improves care quality and lowers the cost of health care delivery for chronically or terminally ill patients, according to the Center to Advance Palliative Care and the National Palliative Care Research Center. "America's Care of Serious Illness: A State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in Our Nation's Hospitals" was published jointly by the centers in 2019. It says 72% of U.S. hospitals with 50 or more beds had a palliative care team. That was up from just 7% in 2001.

—JULIE MINDA